I am nearly done reading Joanne Freeman’s “Affairs of Honor”, which I have been meaning to get to for a couple months now and I wish I hadn’t waited so long because it’s such an impressive and enlightening book.

I haven’t time to write out a full review, and really there is far too much information to condense it all into a comprehensive summary right now, but I will highly recommend it to anyone seeking a thorough history of early American politics. It does not concern battles or the formation of government, but rather the way that the solemn and serious code of personal honor colored so much of the way politics worked and evolved. A man’s reputation was worthy of risking his life, because honor was seen as the bedrock of a civil society.

That said, the newspapers, pamphlets, letters, and broadsides (posters) of the time were commonly filled with gossip, rumors, and outright lies, and there was no system in place to prevent anything from being printed at the whim of a publisher, particularly if it suited their own political goals. Much of these essays were printed anonymously, so the author did not have to answer for his slander. Also, the mail — the only form of direct communication outside of face-to-face conversation — could be highly insecure and unreliable, leaving letters at the mercy of anyone who wished to just hand them to a newspaper for printing, for instance. Men with the greatest amount of power employed personal couriers to avoid the “miscarriage” of their correspondence.

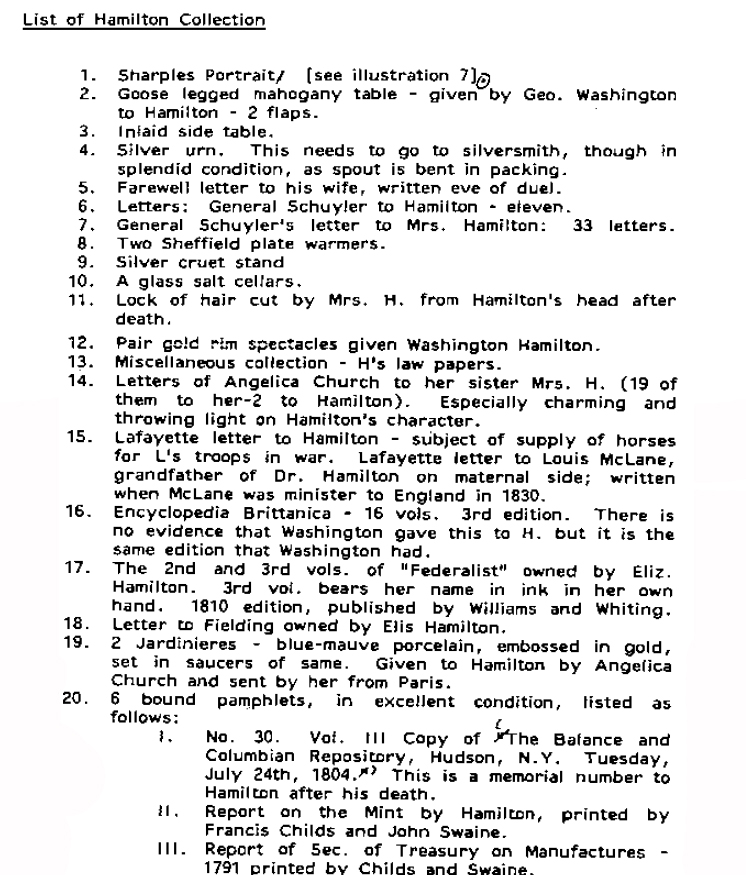

An important piece in the book is Freeman’s thorough examination of the reasoning behind the Burr-Hamilton duel, in chapter four, an event that is constantly misinterpreted by modern times. I think it notable that she waited until the final third of the book to delve into it; after reading the prior three chapters, it makes a lot more sense — in the context of the period, anyway. Hamilton’s statement of July 10, 1804 wherein he explains (in a numbered list because he can’t help himself) all the reasons he doesn’t wish to go through with the interview, but then counters that with all the reasons why he must, is still heartbreaking to read, and particularly to see in his own unusually tight handwriting. Try to imagine his mental state at the moment he was putting those words to paper. This was a man who lived and breathed, and was still a poor kid from Nevis, who had a wife and seven children who needed him, and still felt it was his duty to go through with a duel, knowing that his next day might be (and was) his last. His reputation, and that of his political ideals, must be preserved.

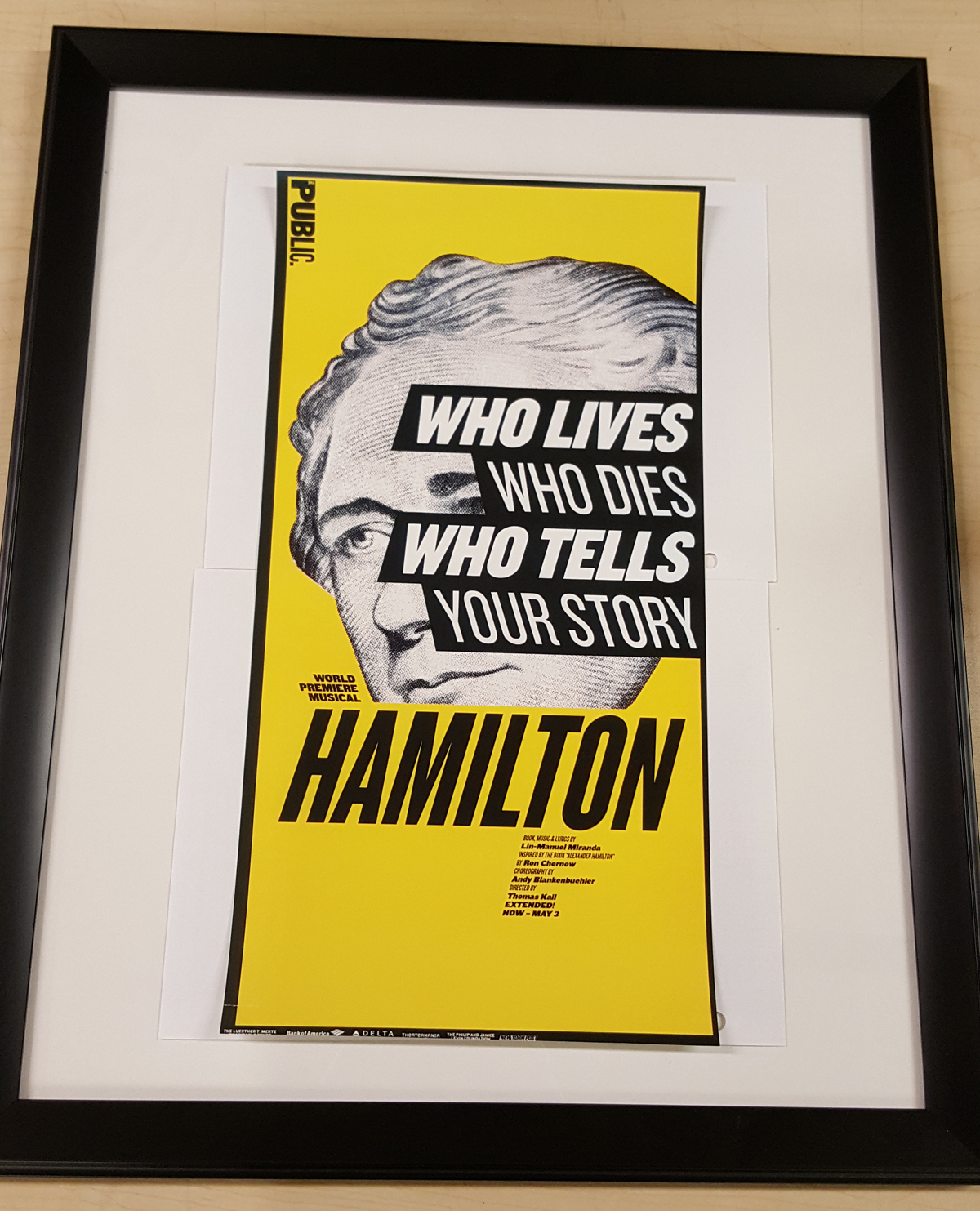

Another part of the book I enjoyed was the assessment of the behavior of John Adams, describing why in the world he did the things he did. Vain, emotional, and obsessed with his reputation and his legacy, his career is littered with political mistakes borne of those characteristics. For example, in 1800, Hamilton published an infamous and lengthy pamphlet that more or less cut Adams to pieces. It is now seen as one of the biggest mistakes Hamilton ever made, and an example of how he let his pride cloud his choices. In the play, “Hamilton”, Miranda mentions it briefly, but never does he tell the audience why Hamilton wrote this pamphlet (he also says Adams fired him, which is just 100% false). In fact, Hamilton had previously written several letters to Adams, asking him to explain his shit-talking, and using coded language that demanded satisfaction. When Adams gave no response whatsoever, Hamilton was deeply insulted and the gloves were off. John Adams was a non-confrontational blowhard. He was also accused of cowardice when he waited nine full years (and five after Hamilton was in his grave) to respond to the pamphlet, writing weekly columns for a Boston newspaper in which he dragged a dead man through the mud, for three years. He succeeded in proving every accusation Hamilton had leveled — that he was a hysterical, petulant, hypocritical, stubborn fool.

But, as much as I am loathe to admit it, these two men shared certain things in common. Later on in life, the former president had a moment of contrition, and I wonder what it would have been like if Hamilton had said the following words instead of Adams: “[there have] been very many times in my life when I have been so agitated in my own mind as to have no consideration at all of the light in which my words, actions, and even writings would be considered by others.”